Reflexiók - Időrendben

Itt a levélben és a Facebook-on kapott, a házakhoz kapcsolódó történeteket és leírásokat lehet elolvasni. Köszönjük, hogy reflektáltak!

2018. június 20., szerda

Nagyszüleim: Galvács István, Galvács Istvánné sz. Schwartz Lenke és Anyám éltek ott, kb. 1939-1968 között. A 60-as évek lakóit mind ismertem. Weinberger család, (Weinberger bácsi rabbi volt), a harmadik emeleten Török (Tiroler) néni, a másodikon Bakonyi Pál, Bakonyiné Vince Ágnes Bien néni és bácsi és Benedikt Ilus. A Bien házaspár lánya és veje is a házban lakott Vadász volt a családnevük, a férfi meghalt a lágerben, felesége valamikor 1945 augusztusában keveredett haza, szintén valamelyik lágerből. Ott élt Gadányi házaspár mindkettőt deportálták - nem jöttek haza Auschwitzból. Anyám úgy emlékszik, hogy ez a ház végül is nem lett csillagos ház... Amit még tudok, hogy nem zsidó nagyapám - Galvács István - néhány hétig két zsidó nőt bujtatott a lakásban, de a házmester megtudta - feljelentéssel fenyegetőzőtt. Bár nagyapám a házmestert megverte emiatt - a két nőnek el kellett hagynia a lakásunkat. Úgy tudjuk, nem élték túl a háborút.

Ha valakinek rokona ismerőse lakott a házban őrülnék ha jelentkezne!

2018. január 16., kedd

Nagymamám, a most 89 éves Krasznay (született Baradlai) Erzsébet többször mesélt nekünk arról, hogyan élte át a háborút keresztényként a Hajós utca 13-15. alatti csillagos házban. Hétvégén újra előjöttek az emlékei, amit kihasználva felvettem az elbeszélését, illetve kicsit beszéltettem is a ház történetével kapcsolatban. Fogadják szeretettel a fenti „oral history-t”, illetve ha valamilyen egyéb adat, információ is érdekes lehet a házzal kapcsolatban, keressenek meg nyugodtan!

2017. szeptember 05., kedd

Budapesten születtem 1928. augusztus 27-én, a Fővám tér 2-3-ban laktam.

1944. június 21.

Szüleim, Kertész István és Czettel Rózsa, jó barátai voltak Halbrohréknak, akik a második emelet 6-ban laktak. Az összeköltözködéskor két szobát kaptunk az első emeleten. Többek közt ott lakott Székely Éva, aki naponta töbször járt fel alá az öt emeleten, hogy trenírozzon. Már arra gondolt, hogy úszóbajnok legyen a következő olimpián. Én két évvel fiatalabb vagyok, de sportból vele tartottam. Éva 1946-ban úszóbajnok lett. Én meg a munkatáborba menéskor Szálasi parancsára jól bírtam Pécelig a gyalogutat. Ott ismerkedtem meg Lengyel Gabival, Kórody, Szász és még egy párral. Nem hallotam többet róluk.

Gabival voltunk az Operában engedély és sárga csillag nélkül.

Egy bombatámodáskor a Visegrádi es a Katona József utca kereszteződésében bomba robbant. Nagy krátert csinált, ha egy kicsit odébb esett volna talán nem írnám ezt a visszaemlékezést.

Október 16-án a Szálasi kormány behívta 16 és 60 év közötti férfiakat munkaszolgálatra. Pécelig gyalog kellett menni. Ott tankcsapdát ásattak velünk és csak egy hét múlva kaptunk élelmet. November elején jött egy orosz támadás; éjjel felébresztettek és erőltetett menetben visszavonultunk hátizsákkal, hálózsákkal és lapáttal a kezünkben. Akik nem bírták az iramot, azt agyon lőtték. Budafokra értünk és a következő reggel Wallenberg keresett minket mint svéd védelem alatt állókat, így menekültünk meg, apámmal együtt. Visszakerültünk a Visegrádi utca 9-be. Másnap még egyszer keresték a 16 és 60 közötti férfiakat; de sikerült elbújni. Szüleim elhatározták, hogy egy svéd védett házba költözünk.

November végén költöztünk be a Katona József 21-be. Ez lett a vesztünk.

Örültünk, hogy kaptunk egy szobát, pár héttel később egy barátom és a szülei, Vigdorovits Artúr építészmérnök, majd közös barátaink, Szabóék is a mi szobánkba zsúfolodtak. December vége felé már lehetett hallani az ágyudörgést Újpest felől.

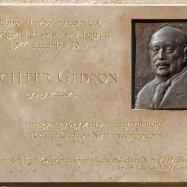

December 30-án a nyilasok nem tisztelték a ház extra-territorialitását, a svéd védettséget. Mindnyájunknak az Andrássy út 60-ba kellett mennünk. Köztünk volt Richter Gedeon gyógyszergyáros is. Őt, a szüleimmel és hatvan emberrel együtt a Dunába lőtték. Nekem sikerült a sorból kikerülnöm. Értesítettem Raoul Wallenberget. A hadügyben azt ígérték neki, hogy nem lesz baj, de mikor a helyszínre ért, és kérdezte hol vannak a védettjei, azt a választ kapta, hogy “a büdös zsidók 10 perce a Dunában vannak”.

Hatan ki tudtak úszni, a rendőrök segítettek kijönniük a hideg folyóból. A szüleimet keresve egy svéd szanatóriumban találtam meg az egyik túlélőt, aki könnyek közt mondta mi történt az apámmal: az első világháborús sérüléséért vaskeresztes kitüntetéses hadirokkant főhadnagy 50 éves korában így fejezte be életét. Anyánknak az Andrássy út 60-ban felajánlották, hogy ha segít főzni, jó bánásmódban lesz része. Sajnos hitt nekik, de az utolsó nyilas, hogy fel ne ismerjék, mindenkit megölt. 47 éves volt, középiskolai tanárnő, később panziótulajdonos a Fővám tér 2-3-ban és Balatonbogláron, az Éden Panzióban.

[Kertész Tamás 1949-ben húsz évesen, rokonait követve Argentínába emigrált. Ma is ott él gyerekeivel és unokáival, az utóbbi időben gyakran tesz eleget iskolai meghívásoknak és meséli el az üldöztetés személyes történetét.]

Budapesten születtem 1928. augusztus 27-én, a Fővám tér 2-3-ban laktam.

1944. június 21.

Szüleim, Kertész István és Czettel Rózsa, jó barátai voltak Halbrohréknak, akik a második emelet 6-ban laktak. Az összeköltözködéskor két szobát kaptunk az első emeleten. Többek közt ott lakott Székely Éva, aki naponta töbször járt fel alá az öt emeleten, hogy trenírozzon. Már arra gondolt, hogy úszóbajnok legyen a következő olimpián. Én két évvel fiatalabb vagyok, de sportból vele tartottam. Éva 1946-ban úszóbajnok lett. Én meg a munkatáborba menéskor Szálasi parancsára jól bírtam Pécelig a gyalogutat. Ott ismerkedtem meg Lengyel Gabival, Kórody, Szász és még egy párral. Nem hallotam többet róluk.

Gabival voltunk az Operában engedély és sárga csillag nélkül.

Egy bombatámodáskor a Visegrádi es a Katona József utca kereszteződésében bomba robbant. Nagy krátert csinált, ha egy kicsit odébb esett volna talán nem írnám ezt a visszaemlékezést.

Október 16-án a Szálasi kormány behívta 16 és 60 év közötti férfiakat munkaszolgálatra. Pécelig gyalog kellett menni. Ott tankcsapdát ásattak velünk és csak egy hét múlva kaptunk élelmet. November elején jött egy orosz támadás; éjjel felébresztettek és erőltetett menetben visszavonultunk hátizsákkal, hálózsákkal és lapáttal a kezünkben. Akik nem bírták az iramot, azt agyon lőtték. Budafokra értünk és a következő reggel Wallenberg keresett minket mint svéd védelem alatt állókat, így menekültünk meg, apámmal együtt. Visszakerültünk a Visegrádi utca 9-be. Másnap még egyszer keresték a 16 és 60 közötti férfiakat; de sikerült elbújni. Szüleim elhatározták, hogy egy svéd védett házba költözünk.

November végén költöztünk be a Katona József 21-be. Ez lett a vesztünk.

Örültünk, hogy kaptunk egy szobát, pár héttel később egy barátom és a szülei, Vigdorovits Artúr építészmérnök, majd közös barátaink, Szabóék is a mi szobánkba zsúfolodtak. December vége felé már lehetett hallani az ágyudörgést Újpest felől.

December 30-án a nyilasok nem tisztelték a ház extra-territorialitását, a svéd védettséget. Mindnyájunknak az Andrássy út 60-ba kellett mennünk. Köztünk volt Richter Gedeon gyógyszergyáros is. Őt, a szüleimmel és hatvan emberrel együtt a Dunába lőtték. Nekem sikerült a sorból kikerülnöm. Értesítettem Raoul Wallenberget. A hadügyben azt ígérték neki, hogy nem lesz baj, de mikor a helyszínre ért, és kérdezte hol vannak a védettjei, azt a választ kapta, hogy “a büdös zsidók 10 perce a Dunában vannak”.

Hatan ki tudtak úszni, a rendőrök segítettek kijönniük a hideg folyóból. A szüleimet keresve egy svéd szanatóriumban találtam meg az egyik túlélőt, aki könnyek közt mondta mi történt az apámmal: az első világháborús sérüléséért vaskeresztes kitüntetéses hadirokkant főhadnagy 50 éves korában így fejezte be életét. Anyánknak az Andrássy út 60-ban felajánlották, hogy ha segít főzni, jó bánásmódban lesz része. Sajnos hitt nekik, de az utolsó nyilas, hogy fel ne ismerjék, mindenkit megölt. 47 éves volt, középiskolai tanárnő, később panziótulajdonos a Fővám tér 2-3-ban és Balatonbogláron, az Éden Panzióban.

[Kertész Tamás 1949-ben húsz évesen, rokonait követve Argentínába emigrált. Ma is ott él gyerekeivel és unokáival, az utóbbi időben gyakran tesz eleget iskolai meghívásoknak és meséli el az üldöztetés személyes történetét.]

Richter Gedeonról

Sikeres pályafutását végül a zsidótörvények megaláztatásai, majd a második világháború eseményei törték derékba. Zsidó származásának – külsőleg egyébként nem érzékelhető – puszta ténye miatt 1942-ben meg kellett válnia vezérigazgatói tisztségétől, és évekig tartó szélmalomharcra kényszerült, hogy alapító tulajdonos létére legalább tanácsadóként dolgozhasson a saját vállalatánál. A magyar gyógyszeripar világhírű, ám itthon „nemzetidegen”-nek minősülő alakja mellett többek közt a Vatikán is kiállt, amikor 1943-ban Angelo Rotta pápai nuncius (nagykövet) meglátogatta a gyárat és a pápa személyes köszönetét tolmácsolta Richter Gedeonnak a sok háborús jótékonykodásáért. A német megszállás után, 1944 nyarán svájci útlevéllel elhagyhatta volna az országot, de nem élt a lehetőséggel, mert nem akart megválni hazájától és kötelességének tartotta, hogy a nehéz időkben is kitartson vállalata mellett, amely életművét, és családja mellett élete értelmét jelentette. Mélységes humanizmusától vezérelve alaptalan bizakodással ítélte meg saját helyzetét, és belekapaszkodott abba az illúzióba, hogy neki nem eshet bántódása, mert ő nem ártott senkinek, ő csak segített a beteg embereken. Évtizedekig homály és hallgatás fedte, hogy pontosan mi is történt vele 1944 tragikus telén. A legújabb kutatások szerint a nyilas hatalomátvételt követően a Richter házaspár egy ideig rokonoknál húzta meg magát, majd 1944. december elején a hatósági rendelettel kijelölt ún. nemzetközi gettóba, a semleges svéd követség diplomáciai oltalma alatt álló Katona József utca 21. sz. alatti sarokházba költözött. 1944. december 30-án a ház lakóit egy nyilas osztag igazoltatás ürügyével az Andrássy út 60. sz. alatti pártházba (a mai Terror Házába) hurcolta. Az épületben a csoportot kifosztották, fogva tartották, majd másnap a hajnali órákban fegyveres kísérettel útnak indították a Duna irányába. A folyó közelében egy mellékutcában a menetoszlopot megállították, az élen haladó férfiak közül az első ötven embert, köztük a 72 éves Richter Gedeont elvezették, és a mai Széchenyi rakparton, a Zoltán utca torkolatánál a Dunába lőtték. Richter Gedeon holtteste nem került elő, jelképes sírja a svájci Lugano városkában, családi sírboltban található. Fél évszázaddal későbbi nekrológjának egyik tömör megállapítása akár a sírfelirata is lehetne: „Igaz ember volt, tudta, mi a tisztesség, maradandót alkotott és neve összeforrt alkotásával.”

Forrás:

https://www.richter.hu/hu-HU/sajtoszoba/Pages/Kozlemenyek/pr091207.aspx

2017. augusztus 17., csütörtök

It was Blimcsu who was the first to suggest that, to ease the financial pressures on the family, she and Lilly should perhaps leave home and fend for themselves in Budapest. Their Uncle Gedalia and others questioned the wisdom of this but their father Baruch said he trusted his girls and that they could go, displaying a remarkably liberal attitude for an Orthodox father. Lilly’s cousin Aranka Mauskopf, who although older than Lilly, was of the same build and thought to look very much like her, gave her a dress before she and Blimcsu set off, arriving on or around March 21st 1943.

Budapest was then still thought to be a haven for Jews. After their eldest brother Jakub had left for Palestine, his wife Malka also needed work and moved to Budapest, initially leaving their three children with her parents in Huszt. Later, when she obtained a job at an orphanage, her two elder children were able to join her, while the youngest remained with his grandparents. They would have travelled to Budapest by train, across the Great Hungarian Plain via Debrecen, early in 1943 and when Lilly and Blimcsu arrived they spent their first night in Budapest at the orphanage where Malka had a room of her own.

Neither Lilly nor Blimcsu had ever used an inside flushing lavatory before and weren’t sure how it operated. On first encountering one and having pulled the chain, they were so surprised at what happened that they ran out and shut the door! Similarly, they only saw coal for the first time when they moved to Budapest.

Blimcsu was an accomplished seamstress, but neither she nor Lilly could find work in Budapest at first. Although both girls may have been aware of, or even have witnessed, the twice yearly ‘servants fair’ in their home town, it is hardly surprising that when they experienced the hiring fair in Budapest for the first time it should feel much like a slave market. Those who were successful in being hired also received their board and lodging and some girls were fortunate enough to enjoy a good relationship with their employer. But, for many, long working hours, under payment and physical and mental abuse were common and some wound up working on the streets.

Lilly’s first prospective employer was a man, who took her to his house where there appeared to be no woman around and so she left at once.

Blimcsu and Lilly were, quite naturally, wishing to stay together if possible and to find work in an observant, kosher home. Initially, they both worked as maids, living with well-off families and working in the home for their board and lodging but without being paid. Blimcsu was hired by a family called Klein, a very nice couple who treated her well, with just one child, a very intelligent boy named Ivan. Their home, in which Mrs Klein’s parents also lived, was in Pest on the eastern side of the Danube. They were Orthodox Hungarian Jews and the husband was active in the Great Synagogue. They were a rich and sophisticated family, very different from those in Huszt.

Not far away in Buda, Lilly managed to get a job with a modern Orthodox couple who had two children. They owned a car and every morning, when the father left to drive to work, Lilly remembered the affection with which his wife would see him off. The house was in Buda, at Gϋl Baba utca 13, a cobbled street in the 2nd District, one of the steepest in the city, a short walk from the Margit Bridge and named after an Ottoman Turk from the 16th century whose tomb and mosque nearby is a national monument and place of Muslin pilgrimage. Lilly recalls that they had a most beautiful piano. Blimcsu would come to meet Lilly and, one day, they were window shopping, admiring the display in a pastry shop, but couldn’t afford to buy anything. Who should come along but Malka’s son Zvika, aged just 14 and living in the orphanage, with a slice of poppy seed cake which he gave them. It is believed that he contracted pleurisy at some point during the war, in all probability whilst he was in Budapest.

On another occasion, they happened to see a man on the street, pushing away a girl who had approached him. Not understanding what had happened, they told a woman at their apartment block about the incident and she explained that the girls was prostitutes, of which neither Lilly nor Blimcsu knew anything. Later, they learned that there had been prostitutes working in Chust, especially in and around the Korona Hotel.

However, Lilly only worked there for perhaps two or three months as she became ill with a chest infection, returned home with Blimcsu and was nursed back to health my her mother. Once Lilly was fit again, the two sisters travelled back to Budapest and Lilly found a new job with a couple named Lӧvinger in Pest, who had two children, a boy aged nine and a girl of five whom Lilly thought looked like Shirley Temple!. It was a large apartment in a block at Aréna út 17, near Városliget Park (now Dózsa Gyӧrgy út 17), in the XIV District of the city, a very smart, expensive-looking building with parquet floors that Lilly cleaned, waxed and polished and in which she occupied the maid’s room. As well as other housework, she also did the laundry, entirely by hand, waited at table and washed the dishes. She was supposed to have Sunday off but still had to do the laundry first. Afterwards, she would explore, walking around the city.

On one occasion, Lilly had taken the younger child to the park and, whilst playing on the swings, the girl was hit in the face and was bleeding. Lilly was mortified that she might be seriously injured and was fearful of the consequences. However, Mrs Lӧvinger was very understanding and all was well.

Meanwhile, Blimcsu had been working in a ‘sweatshop’, making dresses, blouses and coats and, after a few weeks, managed to arrange for Lilly to join her there. They were up on the 6th floor, with little ventilation, being unable to open the windows. The radio played classical music all day, much of which Lilly managed to memorise. There were about twenty to thirty girls employed there, most of them also refugees from Carpatho-Ukraine, each working on their own particular jobs such as sewing buttons or seams. On one side, Lilly had a girl from Seylesh and on the other, from Mukachevo. All were on piecework. As sisters, Lilly and Blimcsu weren’t permitted to sit together and initially it was the other girls who helped Lilly.

However, with her lack of sewing skills, she was moved onto ironing finished clothes, mainly blouses. Lilly worked ten hours a day, standing whilst pressing clothes with a heavy electric steam iron, the power cable for which hung down from the ceiling. The only girl from their home town who was working there was Lilly’s school friend Rozika Liebovič, whose father produced soda syphons. She took the name of Glϋck when in Budapest, perhaps because it sounded much less Jewish.

They could now afford to pay for a room in the apartment block, becoming tenants and remaining there until the following year. Lilly recalled that, at least once or twice, she and Blimcsu went to the theatre to see a musical production, paying just one pengo to stand high up at the back of the auditorium .

Food supplies had become very short and they saved money by walking, rather than taking the tram on the Rákóczy ut route, so that they could have a little more to spend on food. They kept in touch with home by post and once their father Baruch sent them a loaf. Unfortunately, because of the length of time it took to reach them, the bread was mouldy but they nevertheless cut off the outside and ate the rest. Now they were both working, they sent money home to help the family, collecting offcuts of white cotton material which were also sent back for use in making shirts for their brothers.

Downstairs at Aréna út 17 lived at least two, and possibly up to four, young Frenchmen. It is thought that at least four thousand French prisoners, both civilians and military, had escaped to Hungary and many made for Budapest. They were hiding or being hidden in houses across the city. Those at the apartment block only spoke French and the two girls knew nothing about them and, with one exception, had nothing to do with them. One of the Frenchmen, they later discovered, was named Andre Buchet and, unlike his compatriots, was able to speak a few words of Hungarian. He was aged 34 and showed them a photograph of his wife. He also had his own camera and took several pictures of Lilly and Blimcsu. Another resident was Latabár Kálmán, a Hungarian comedian and film actor, perhaps the country's most popular comic in the post-war years. Known as Latyi, he reached his peak popularity during the wartime period and had already starred in three films. After the war, he made several successful tours in Western Europe, Israel and America, idolized by the émigré Hungarian community.

German forces had occupied Hungary on Sunday March 19th 1944 and in Budapest, around six o’clock that morning, large numbers of aircraft appeared, flying over the city. By the time Lilly and Blimcsu were up, the entire city had been overrun by the Germans, with the police headquarters, the General Post Office and radio stations all taken over. With the Palace surrounded by German troops, the Regent and head of state Admiral Miklós Horthy was powerless to oppose the occupation and, a few days later, Nazi sympathiser General Sztójay was appointed as head of the government. Within a week, all prominent Jewish businessmen and others who held important positions in Budapest were either arrested or deported to Germany and the city was certainly no longer a haven for the Jewish population..

Allied bombing of Budapest had begun with the US Army Air Force on the night of April 2nd 1944 and by British aircraft on the following night. Targets included the rail yards of Pest, the armament works at Csepel and the Thӧkӧl aircraft components factory.

Also, on April 5th, the first yellow stars appeared on the streets, sewn on the front of coats or other outdoor clothing to comply with the latest order from the Germans. Any Jews who had learned what had happened in other places following the introduction of the yellow Stars of David, would have become very fearful for their future, but nevertheless the majority obeyed the order and some stores began selling clothes with the stars already attached. Indeed, Lilly observed that, in the photographs that show her wearing her yellow star on the street, she appears relaxed and smiling.

However, this was just the latest action of the German occupiers, with posters pasted to walls throughout the city, listing the many activities which were now forbidden and punishable by death, just as they had been in Huszt.

By April/May 1944, having learned of the ghettoization in Huszt, the two sisters felt they should at least try to get back home to their family. They went to Keleti station where a large crowd of people had gathered, hoping to board trains but, as most were wearing their yellow stars, Hungarian police began opening fire on them and, in the resulting mêlée, Lilly’s friend Rozika Liebovič was killed.

On June 16th, the Mayor of Budapest issued a decree, designating almost two thousand apartment buildings across the city as so-called ‘Yellow-Star Houses’, in which some 220,000 Jews were to be concentrated. The scheme was planned by László Endre, the architect of the deportations from Huszt the previous month and the buildings chosen were those in which at least 50% of the tenants were Jewish. Having been ordered to vacate their own homes by midnight on June 21st, after that deadline Jews were forbidden to live anywhere but in a Yellow-Star House. In the majority of cases, families were only entitled to occupy one room and under no circumstances was a Jewish family permitted to have more than two rooms, irrespective of its size or the physical needs of individuals.

However, the magnitude of the task proved impossible to complete in the limited time available, with many thousands of Jews having to move themselves and all their belongings to their newly designated homes. A few days later, still more new restrictions were imposed on the Jewish population, preventing them from entertaining guests in their apartments, obliging them to travel in the rear section of the city’s trams and banning them from Budapest’s parks and promenades.

This concentration of the Jewish population in known locations throughout the city was clearly in preparation for eventual deportation and the fate that had already befallen those in the provinces and the countryside. However, Lilly and Blimcsu seem to have been completely unaware that their apartment block at Aréna út 17 was now designated as a Yellow-Star House and Lilly had no recollection of the special signs that would have appeared on every entrance to the building, a 12 inch (30 cms) diameter canary-yellow Star of David on a black background 20 ins by 14 ins (51 cms x 36 cms).

Allied air raids on the city continued, including British Royal Air Force night bombing operations to drop hundreds of mines along the River Danube, while Boeing Flying Fortress and Consolidated Liberator heavy bombers of the US Army Air Force maintained daylight attacks on military targets around the city. During one daytime air raid, the window of the girls’ room was blown out whilst both of them were in the room.

In September 1944, whilst working in the sweatshop, Lilly became ill once again, with a high temperature and swollen legs, probably not helped by spending long hours standing at the press. Blimcsu returned from work to find her in bed and, having put a thermometer in Lilly’s mouth to take her temperature, fell fast asleep exhausted by her side. When she awoke, the thermometer was still there!

Mrs Lӧvinger called a doctor, who happened to be Jewish and was probably her own doctor for herself and her two children. He took her in his car and checked her into a hospital, where there were many injured from the bombing. Her sister-in-law Malka came to visit her in hospital on her own during the daytime bombing and Lilly showed her a leaflet that a nurse had given her. This made Malka laugh and she explained that it was warning prostitutes about the health risks and only then did Lilly realise that she was on the ward for venereal disease patients and that she was the odd one out! Lilly was also the only one confined to bed, the other patients being up and about…and seeming surprisingly happy. She was very confused!

As far as was possible, Lilly and Blimcsu never allowed themselves to be separated, so fearful were they of being left on their own. They went to the lavatory together and, if there was an air raid and there wasn’t sufficient room for them both down in the cellars, they would stay in their room, even if the windows were blown out. They were inseparable, each looking after the other.

The wailing of the air raid sirens and the sound of bombs exploding across the city were now so commonplace that Lilly and Blimcsu, up on the second or third floor of the apartment block, had become accustomed to this way of life and no longer always sought shelter in the cellar. This was used both as a coal store and as a place in which families would keep possessions for which they had no room in their apartments. While the air raids were taking place, everyone would sit around on boxes and, on one occasion, the father of one of the families shared a handful of raisins with them, for which they were very grateful.

Nearly 40% of the buildings in Budapest had been damaged or destroyed in the British and American air raids before the siege by the Russians, Districts IX and XII being the worst affected. This further depleted the city’s Jewish population which, with emigration, deaths from forced labour introduced in 1941 and the actions of the Arrow Cross militia, is estimated to have been halved.

Mr Lӧvinger had already been taken to a labour camp and the children too had left for England, possibly with the help of a Swiss rescue group and it is believed they survived. Lilly now began to feel greater sympathy for his wife, being able to relate to her changed circumstances.

Two nuns came to the block and offered to convert the older women to Catholicism. Only one did so, although it made no difference in the end. One day, probably during the third week of October 1944, they were at home in the apartment block when men with machine guns arrived, most likely a mix of police and Arrow Cross militia and, using a megaphone from the courtyard at the rear, ordered everyone, including any ‘converts’, to leave the building. They were allowed to take some clothes, food and a blanket, but everything of value was to be left behind. They were told that if any valuables were found on them, they’d be shot and, if they couldn’t tell who was responsible, one person in ten would be shot.

Overall, the Arrow Cross was responsible for the reduction of the Jewish population of Budapest by an estimated 100,000 or more between October 1944 and February 1945. Murders took place all along the Danube Embankment and in Varosliget Park, near where Lilly and Blimcsu had been living. So many bodies had piled up on the park benches in November, it took several days to remove them all.

On October 18th, Eichmann had reappeared in Budapest. Hans Geschke of the Gestapo, the man responsible for the destruction of Lidice, was made Head of the SD in Hungary and eliminating the country’s Jews seemed more important than anything else, even perhaps the winning of the war.

Mrs Lӧvinger always kept a great many things under lock and key, including food and drink. However, they were able to gain access to the locked pantry and amongst the food they took with them were items such as sardines, chocolate and little portions of roux that she made in advance for use in sauces. But before they left, Andre Buchet, the young Frenchman who lived downstairs, took more photographs of Lilly and Blimcsu, although how they received the prints and, more importantly, managed to hold on to them until their liberation, remains a complete mystery.

It was raining and cold as they were marched to the Great Synagogue in Dohány Street, the largest in Europe. The streets were lined with crowds of people, mainly women, who clapped as they went past, shouting abuse and rejoicing in their fate. On arrival at the Great Synagogue, they were told that they would be leaving the next day and would not be permitted to take any food with them. Consequently, everyone ate absolutely everything they had brought by way of food and, as a consequence, many became ill. With only two lavatories, one for men and the other for women, conditions quickly became very bad indeed. An estimated seven thousand died there during the winter of 1944-45 and were later buried in the grounds.

The next day they were marched out of the synagogue whilst the city was being bombed, over the Margit Bridge, most probably towards the Nagybátony-Újlaki United Factory/Brickyard at Óbuda, one of a chain of brickworks established along Bécsi út since the 1860s and the largest of the transit camps in the autumn of 1944. There was no food or water and the weather was very cold. While Lilly recalls that they were under cover, with her resting her head in Blimcsu’s lap, it’s not clear whether they were in one of the brick-drying barns with a roof but no sides or elsewhere.

For the next several days, they were told to line up and were marched back and forth, five or six abreast with Hungarian Fascist Arrow Cross guards on each side, to the Jozsefvarosi freight station to take them to Austria. However, there were no trains available and, each time, they were marched back to the brickyard. This would have been a three-hour 15km round trip in freezing conditions. People were shot at random and their bodies thrown in the Danube. Lilly and Blimcsu were soaking wet, very cold and, carrying a sodden blanket, lacked the strength to carry anything else. Although the police were supposed to keep order, the real power was in the hands of the Nyilas, Arrow Cross Party members, who robbed them of their valuables, clothing and any other supplies they might have had.

Most of the 70,000 Jews taken to the Óbuda brickyards were marched towards the Reich frontier at Hegyeshalom, the Hungarian checkpoint on the road to Vienna, a journey of between 200 and 230 kms that would have taken seven or eight days. There was little or no food, at best three or four portions of watery soup throughout the entire march and members of the Swiss Legation and even several senior war-hardened SS Generals were shocked by the sheer brutality with which the marchers, men, women and children, were treated.

However, Lilly and Blimcsu were instead marched down to the river, possibly to the unfinished Arpad bridge to be loaded on an open barge, where they stood, packed with other women and were taken 15 miles (24 kms) up the river to a camp on Szentendre Island, near the villages of Horány and Szigetmonostor, close to the small town of Szentendre on the west bank of the Danube. The vessel was dangerously overloaded and several of the women fell in and were drowned.

The camp consisted of wooden barrack blocks, once a centre for young people. Because it was designed for children, the beds were short and they slept on straw bedding. Between November 18th and 21st, there were approximately 500 in the camp, but by the 29th, this had swelled to 1200. Each day, they were woken before dawn, marched in the dark for about an hour to dig ditches up to six feet (1.8 metres) deep as anti-tank defences. Such ditches, on an island in the Danube, can have had little strategic value and were simply another example of pointless hard labour, used as a means of degrading those involved. As the ditches became deeper, it became increasingly difficult for the women to throw out the soil.

From time to time, they were forced to stand in line to be given filthy water. Many girls fainted or collapsed and the Hungarian Arrow Cross guards on horseback would shoot them. Blimcsu frequently had to pull Lilly up when she was too weak to stand and would talk to her to keep her going. However, at one point, an elderly Hungarian guard, probably a reservist who went home at the weekends, did bring them an apple.

One day, while they were marching, they came across a group of men and recognised one of them as having come from Huszt, who told them of the deportations and said there was no-one left there.

As was the practice in all the camps, there were constant roll-calls, where they were lined up and frequently ordered to give up any valuables they might have and told that, if they failed to do so, every tenth woman would be shot. Blimcsu had hidden some precious items, such as a watch and a pair of the tiny gold ‘sleeper’ earrings that used to be given to babies a few weeks old, under the thread on a spindle and Lilly was worried that, if their barracks were to be searched, they would be found. However, it was never discovered. There were also other threats and, on one occasion during roll-call, the German who was in charge told the guards that if any of the men had “mixed their blood” with the prisoners, he would shoot them dead.

Conditions in the camp continued to deteriorate. After the day’s work, there was a thin soup in a large vessel, with lumps of speck floating in it. The girls used the fat to protect their shoes from the damp and many became ill in the unhygienic conditions, with no lavatories or washing facilities, other than the river.

However, as the Russian grip on Budapest tightened, by Christmas 1944 the Gestapo and several German divisions had already left Budapest and moved north along the Danube, accompanied by several thousand members of the Arrow Cross Party and their families. A Hungarian Army battalion began retreating from Szentendre Island but subsequently opted to surrender instead. At midday on December 26th, a Cossack reconnaissance unit appeared in the small town of Szentendre, on the west bank of the river, the Russian 25th Guard Rifle Division having arrived on the Island the previous day, followed shortly after by a larger force. The occupation of the Island was completed by January 3rd but, by then, Lilly and Blimcsu were long gone.

They had been lined up for the daily roll-call one morning when Lilly and Blimscu heard their names called out, together with the Hungarian word spanyol, meaning Spanish or spaniard and, much to their astonishment, they were handed citizenship documents that the Frenchman Andre Buchet had obtained for them. These may have been genuine so-called ‘letters of protection’, issued by Ángel Sanz Briz, the Chargé d’Affaires of the Spanish Legation in Budapest. Alternatively, they could quite possibly have been forgeries produced by the underground movement with whom Andre Buchet was working. Whichever is correct, they could well have saved their lives.

Somehow, they managed to make their way back to Budapest to find the ghetto empty. Inside a building in which they sought shelter, everything had been stripped. It was bitterly cold as they searched for any food that had been left behind. Their only possession was a piece of soap, which they used to wash their underclothes at night. However, the superintendent took it away and, ever since, Lilly refused to throw away even the smallest sliver of soap, preferring to cut them up with scissors and put into a bottle of water to make liquid soap! The next morning, the superintendent told them they could not stay there. They were still wearing their yellow stars and were afraid to go out on the streets. Nevertheless, he insisted that they leave at once.

The fighting got closer and closer and, on the night of January 10th, Russian and Romanian troops had crossed the Hungaria Boulevard and entered Városliget Park, just a mile and a quarter (2 kms) from their previous room at Aréna út 17. The 2nd Company of the Budapest Police Assault Battalion, supported by a group of three hundred gendarmes, forced them back but one of their obsolete tanks was destroyed and half the men killed. The exhausted group was pushed back across the park to Aréna út, where a counter-attack supported by two German tanks managed to recapture around half of the park.

Two days later, Aréna út became the front line, with the German Panzer Corps Feldherrnhalle Division facing the Russian forces in Városliget Park, the majority of which was now in Soviet hands.

However, whilst hiding in a basement, the two young women could hear the noise of heavy armoured vehicles and a man who was hiding with them recognised the distinctive sound as that of Russian, rather than German tanks and told them that their liberators had at last arrived. It soon became apparent that the Russians were on the streets and, unlike the Hungarians around them, Lilly and Blimcsu could both communicate a little, having learnt Russian as a second language in the 4th grade at school. They were told Aréna út 17 was ‘safe’ and so removed their yellow stars, although there was shooting going on all around them, with Russian aircraft strafing the city. They sought sanctuary in the cellar of the apartment block but it still wasn’t truly safe, since Russian soldiers were prowling the streets at night, looking for women.

They would never get undressed at night and, on one occasion, climbed out of a window to get away from Russians. At another time, Lilly had to protect Blimcsu from a soldier, challenging him to shoot her, but discovered that he was only armed with a flashlight. On a separate occasion, she hid Blimcsu in a barrel when a Russian appeared. The soldier attempted to strike matches to look for her in the darkened cellar, but was too drunk to do so and eventually left. They were told that their liberators had been given vodka and three days of so-called ‘rape leave’.

Lilly became hysterical at the lack of action by the other adults in the cellar who didn’t understand Russian. They were advised to cover their heads with a scarf and to tell men that they were ‘sick’ and urged to move on by an older woman before some Russian soldiers, who at first had been friendly and helpful, returned drunk and expected sex. Lilly and Blimcsu had no experience of such things and so they left, under fire from the air while out on the streets, but were unhurt.

They joined a bread queue in the street while Russian planes continued to strafe the city, before finding their way to an area that was already free of Germans and Arrow Cross militia. Once again, they sought refuge in a cellar or bunker with others and found a Jewish man hiding in an ironing board cupboard. There was no electrical power and people were using homemade oil lamps for light.

One day, someone came with news that there were tanks in the streets nearby and, not long after, a Russian officer came down into the bunker and told them they were safe. Unlike the others there, Lilly and Blimcsu were able to understand what he was saying. Knowing of the potential risks they would face at the hands of drunken soldiers who had endured a one hundred day siege and, in all probability, suffered badly during the long campaign against the Germans, a woman told them ‘children, you get out before dark, because you won’t be safe.’

After their liberation on January 17th/18th 1945, a Russian officer came looking for pillowcases, to be used to carry objects looted from nearby houses that would then be sent back home. Another ordered his batman, who was making borsch for his officer, to give some to Lilly and Blimcsu and then whispered to them that he too was a Jew. On another occasion, they were given food that some Russians had ‘liberated’ from stores that were still intact.

Having been completely powerless for so long, liberation released a strong desire in Lilly to fight back in some way, to do something useful and she admitted to imagining, at least for a moment, that she should volunteer to join the Russian Army.

They had returned to the original house in which they’d sheltered. Whenever the soldiers came, they hid in the space between the houses, climbing from the bathroom window until it was safe to emerge. Russians asked them to report anyone who had hurt or mistreated them and they could have denounced the Superintendent who threw them out. However, they decided not to.

Anyone without papers risked being taken away by the Russians for forced labour. A temporary ‘consulate’ was set up where everyone queued for papers. The Czech official asked them to repeat a Czech tongue-twister to prove their nationality. This was “Třiatřicet stříbrných vlaštovky letěl přes třiatřicet střech“. (Thirty-three silver swallows flew over thirty-three roofs). However, they were later stopped by a Russian soldier who, having demanded to see their papers, was unable to read them and promptly tore them up and threw them in the mud. It is unclear whether these were the newly-acquired Czech papers or those obtained for them by Andre Buchet when they were in the forced-labour camp on Szentendre Island.

The Russians opened a ‘camp’ for those who were displaced and Lilly and Blimcsu stayed there in a wooden hut and were given bread to eat. Whilst there, they saw Andre Buchet once more and learnt that his home was in Paris. They also met their sister-in-law Malka, just once, out on the streets where they found her cutting meat from a frozen horse carcass, a not uncommon sight.

Story written by John Berkely, the nephew of the two women, who can be contacted at: gluckpast@gmail.com

____________________________________________________________________________

i., An internal flushing lavatory is still referred to as an 'English WC' in Hungarian.

ii., The Hungarian unit of currency. One pengo would have been worth approximately 25 US Cents.

iii., In what is known in Britain as ‘the gods’, and in the US as the ‘nosebleed section’!

2016. május 21., szombat

Részletek Neufeld Róbert, ”Ahol a földek sírtak” (Där åkrarna grät) című regényéből. A könyv a család 1956 novemberi disszidálásáról szól, de a szerző néhány kitérőben visszaemlékezik az 1944-ben átélt szörnyűségekre, többek között a Népszinház utca 59-es számú csillagos házban eltöltött időre.

“Leginkább nagypapa és nagymama suttogó beszélgetéseiből kezdtem megérteni, hogy mi is folyik körülöttem, hogy mi a háború, kik a németek és kik azok, akik a németek parancsait végrehajtják. Átmentek ugyan egy másik szobába, hogy ne halljam, mit beszélnek, de az elkapott foszlányokból annyit felfogtam, hogy nagyon félnek.

November elején parancsot kaptunk, hogy hagyjuk el Hernád utcai otthonunkat. Apu akkor már régen nem volt velünk. Nem tudtuk hol van, az utolsó levele vagy egy esztendeje jött meg, 109/37 állt rajta, ez a munkaszolgálatos század címe, mondta anyu. Amikor apu bevonult, anyu vette át a munkáját a Korona kenyérgyárban, de 1944 őszétől a gyár nem tudta tovább foglalkoztatni anyut.

Október 15-én a korábban eldugott rádiónkon hallgattuk Horthy Miklós proklamációját. Én nem tudtam, mit jelent az a szó, és amikor rákérdeztem, anyu leintett. Nagyon feszülten hallgatta a rádiót, s a beszéd után sírva borultak egymás nyakába Ilonka nagynénémmel. Vége a háborúnak, mondták lelkendezve, a németek ki fognak vonulni az országból. Hát nem úgy lett.

Amikor a parancs megjött, hogy költöznünk kell, anyu lovat és kocsit kapott kölcsön a Korona pékségtől, hogy át tudjuk szállítani a holminkat a Népszínház utca 59-es számú házba, amely a Teleki tér sarkán állt. Anyu fogta a gyeplőt, mi többiek meg összehúzódtunk a bakon, meg a bak mögött.

Az 59-es ház kapujára egy Magen David, azaz sárgacsillag volt felszegelve. Olyan, mint amilyet mi viseltünk a kabátunkon, csak sokkal nagyobb. Egy csillagos ház, mondta anyu mérgesen. A zsúfolásig teli ház egy második emeleti lakásában kaptunk egy szobát. Amíg anyuék behordták azt a keveset, amit magunkkal hoztunk, én kimentem a gangra. A másik lakás előtt a rácsnál álltak a lakók és nézték az újonnan érkezetteket. Körbementem a gangon. Az egyik lakás bejárata fölött egy kis táblát láttam azzal a felirattal, hogy ”Itt nem laknak zsidók”. Bár még kicsi voltam, már tudtam olvasni. Két lakást láttam ilyen táblával. Az egyikben az Andrádiék laktak, a másikban a Keresztényék. A nevük kis réztáblákon állt az ajtón, csak nem felül, hanem a szokott helyen. Később, amikor már minden lakásba beköltöztek, és mindenki elhelyezkedett, e két lakásból kijöttek a gyerekek, és játszottak velünk.

A házban különben szigorú fegyelem uralkodott. A házparancsnoknak kinevezett férfi a földszinten lakott, egy pár lépcsőn kellett felmenni, ha az ember be akart hozzá kopogni. A házparancsnok nem volt zsidó. Erőszakos, rettenetes ember, mondta anyu Ilonka nénémnek. Többször is hallottam, hogy ezt mondja. Annak az embernek nagy hatalma volt. Úgy jött-ment a házban, ahogy neki tetszett. Benyitott ide is meg oda is, turkált a dolgok között, olykor még a szegényes ételt is megnézte. És ha mondott valamit, annak úgy kellett Lennie. A ránk, zsidókra vonatkozó parancsokat kétnaponta kapta valahonnan, de ezeket gyakran be sem várta, hanem a saját maga parancsait osztogatta. És azoknak pont úgy kellett engedelmeskednünk, mint a hatóság parancsainak. Azzal fenyegette a lakókat, hogy aki nem engedelmeskedik, vagy kihágást követ el, azt azonnal feljelenti. Amikor valami új parancs érkezett, kiállt az udvarra, és a lakása ajtaja mellett lógó rozsdás vasgerendán kolompolt, amíg mindenki ki nem jött a lakásából. Aztán felolvasta az új parancsot és ismét figyelmeztette a lakókat, hogy ”Minden szükséges lépést megteszek azok ellen, akik nem engedelmeskednek”. Mindig ezzel fejezte be.

A házban folyt az élet. Bár nagy volt a zsúfoltság, mégsem emlékszem, hogy nagyobb problémák adódtak volna. Később érett fejjel rájöttem, hogy valószínűleg az állandó félelem volt az, ami féken tartotta az érzelmeket. Hogy mi hogyan tudtunk elférni abban az egyetlen szobában, ott a második emeleten, máig sem tudom.

A front egyre közeledett, nem sokkal a Népszínház utca 59-be költözésünk után megkezdődtek a komolyabb bombázások. Szinte minden nap le kellett menni a pincébe, volt, hogy kétszer is. Én legtöbbször beültem nagyapa ölébe, kedvenc könyvemmel, Pinocchióval a kezemben. Néha kialudt a villany pár percre, amikor egy-egy bomba túl közel talált leesni.

Egy nap, valamikor november vége felé lehetett, a nyilasok berontottak a házba. Én éppen az egyik nem zsidó pajtásommal játszottam. A nyilasok lehettek talán nyolcan vagy tízen, ordítoztak, üvöltöttek, rohantak emeletről emeletre. Mindenkit beparancsoltak a lakásba. Anyu kiszaladt értem a gangra, behúzott magával és becsukta az ajtót. Leültünk. Anyu, Ilona néném és én az ágyra, nagypapa meg az egyetlen székre. Vártunk. Láttam anyun és Ilonkán, hogy nagyon félnek. Nagypapán nem láttam semmi jelét a félelemnek, sőt, ő mondott egy pár nyugtató szót a lányainak. Ilonka odaállt az ablakhoz, és a függöny mögül kikandikált. Hirtelen megfordult és megint leült. Nem sokkal rá dörömböltek az ajtón. Két nyilas jött be, egy fiatal és egy idősebb. Egyszerű civil ruhát viseltek, a puskájuk tusa fényesre volt polírozva. Karszalag volt a karjukon, rajta a nyilaskereszt. A fiatalabb, szőke, megtermett figura, szúrós szemmel méregetett minket. Beállt az ajtóba terpeszállásban, a puskával a kezében, szinte lövésre készen. Az idősebb, apró termetű szótlan ember, benézett a szekrénybe, az ágy alá, az asztalon felemelte a fazék fedelét, belenézett, aztán megállt az egyetlen kép előtt, ami a falon lógott, anyu és apu esküvői képe volt az, anyu hófehér, hosszú esküvői ruhában, apu pedig bonjourban és fehér csokornyakkendőben.

Odafordult hozzánk.

- Ez maga ezen a képen?

- Igen - mondta anyu. És az uram. Ő munkaszolgálatos. Anyu hangja remegett, amikor a nyilassal szembenézett.

- Na jó. Maga most velünk jön. És nagypapára mutatott a puskával. – Szedjen össze pár napra valót, alsóneműt, szappant, meg ami ételt elvihet. De iparkodjon, hallja! Aztán felénk fordult.

- Maguk meg itt maradnak. És meg ne merjenek mozdulni! Megértették?

- Igen, megértettük. Segíthetek az apámnak?

A nyilas bólintott, anyu felugrott, máris kezdett csomagolni. Egy perc alatt készen is volt. Nagypapa odajött hozzám, megcsókolta a homlokomat, aztán átölelte a két lányát és elbúcsúzott tőlük. Nyugodtnak nézett ki, még egy kis mosoly is kiült az arcára, amint a két nyilas között az ajtó felé ment. Anyu kezébe temette az arcát és hangosan sírni kezdett. Ennek láttán én is sírni kezdtem. Ilonka néném nem sírt, ő csak fogta nagypapa karját és csak akkor engedte el, amikor a fiatalabbik nyilas odébb rántotta. Aztán hátba lökte nagyapát és kituszkolta az ajtón. Mikor nagypapa már kint volt a gangon, a nyilas megfordult. Rám mosolygott, és én azt hittem, hogy majd mond valami vigasztalót. De csak azt vetette oda, hogy ”Meg ne mozdulj!”

Ezt értettem. Anyu erősen magához szorított és még hangosabban sírt. Mi ülve maradtunk, ahogy a nyilas megparancsolta. Anyu csak sírt tovább, Ilonka néném pedig elővette a cigarettatöltőjét, s nekiállt cigarettát sodorni. Kinyitotta a fedelet, töltött bele dohányt, aztán a csövére húzta azt a Diadal kettes hülznit, amit mindig használt. Ő sokkal nyugodtabb volt, mint anyu, de hát ő sokkal idősebb is volt nála.

Ültünk az ágy szélén és vártunk. Egyszer csak lövések hallatszottak, több sorozat egymás után. Anyu nagyot sikoltott és Ilonka sem volt már olyan nyugodt. Az arca egyszerre krétafehér lett, leejtette a cigarettatöltőt, átkarolta anyut és a fejét a vállára hajtotta. Láttam, hogy ő is sír. Hosszú percekig így maradtak. Aztán egyszerre csak berontott két másik nyilas puskával. Ránk ordítottak.

Ki innen! Ki innen! Gyerünk, gyerünk!

És kituszkoltak mindnyájunkat a lakásból, le az udvarra. Hamarosan ott állt mindenki. A nyilasok elállták a kapu felé vezető átjárót, hárman pedig fentről, az első emeleti gangról figyeltek minket. Ránk fogták a puskájukat, és hol ide, hol oda céloztak velük. Őket bámultam, anyu meg még jobban magához szorított. Az egyik nyilas rám fogta a puskáját, hosszasan nézett, majd felnevetett, és rám kiáltott ”Megállj csibe, megdöglesz!”

Erre anyu megint sírógörcsöt kapott. A nyilas felröhögött és oldalba bökte a mellette álló társát. Egyszer csak megint ránk üvöltöttek a nyilasok és kezdtek mindenkit kituszkolni a kapu felé. A lépcsőházban iszonyú szag csapott meg, azonnal elhánytam magam. Mikor kifordultunk a pár lépcső felé, ami a kapuhoz vezetett, akkor láttam meg a hullákat. Ott feküdtek véresen, mindenfelé és mindenféle, elképzelhetetlen pózban. Anyu rám borította a kabátja szárnyát és szinte futott velem a kapu felé. Közben egyre csak azt hajtogatta, ”szegény papa, szegény papa”. Az egyik idős lakó, Fagott néni, mellettünk futott és sikítva mondogatta ”a fiam volt, a fiam volt. Kint volt a bele neki, kint volt a bele neki!” Valaki csitította, hogy nem a fia volt, hanem valaki más, de Fagott nénit nem lehetett lecsendesíteni, egyre csak jajveszékelt.

A Népszínház utcából kihajtottak bennünket az Alföldi utcába. Ott már más házakból is álltak lakók. Az úttesten egy tank állt. Az ágyúcső éppen emelkedett. Kisvártatva egy lövést adott le, a szörnyű dördüléstől majdnem megsüketültem. Egy erkélyt találtak el a szembeeső Népszínház utcai házon, nagy porfelhő kerekedett. Két nyilas futott végig a soron üvöltve. “Fel a kezekkel, fel a kezekkel! Egészen Sztálinig!” Oda hajolt hozzám. ”Hallod? Egészen Sztálinig!” Én feltettem a kezemet, de hamarosan elfáradtam és akkor anyu tartotta a kezemet, hol az egyiket, hol a másikat.

A tank megint leadott egy lövést és most a másik fülem is bedugult. Sírva fakadtam. Anyu mondott valamit, de én nem hallottam. Később visszatereltek bennünket a házba. Addigra a holttesteket elvitték, mert a ház előtt és a kapualjban már csak a vértócsákat lehetett látni. Befelé menet anyu már nem takart el a kabátjával. Már nem volt ereje rá, gondoltam. A lépcsőházi vérszagtól megint elhánytam magam. Anyu tartotta a homlokomat, amíg a roham elmúlt, aztán felvezetett a lakásba.

Nem emlékszem, hogy mikor történt, de valamivel később kivezényeltek mindannyiunkat a zuglói KISOK pályára. Ott elválasztottak anyutól, onnan nagymamával mentem a gettóba.

Ilonka nénémet is hozzánk sorolták be, de ő megkérte a nyilast, hogy engedje meg, hogy együtt mehessen a húgával. Így aztán mind a ketten Bergen-Belsenben kötöttek ki, onnan kerültek a felszabadulás után Svédországba.

Apám a munkaszolgálatból ’45 májusában tért haza súlyos betegen. Az őszre felépült és el tudott kezdeni dolgozni, mint kenyérkihordó, a nyolcadik kerületben, egy József utcai sütödénél. Anyuról nem tudtunk semmit, ő sem rólunk. De valamikor 46 tavaszán apu megtalálta a nevét egy névsoron, amit a Vöröskereszt közölt le az újságokban. Így tudtuk meg, hogy túlélte a borzalmakat. Aztán levelezni kezdtek. Anyu azt akarta, hogy mi menjünk ki Svédországba, de apu maradni akart. Ezért anyu 47 novemberében hazajött, de nagyon megbánta. 49-ben megszületett István öcsém. Anyu álma hét évvel később teljesült, visszamehetett Svédországba. Az egész család kiment, 1956 december 10-én érkeztünk. Apu 1985-ben halt meg, anyu 2011-ben követte. István öcsém most 66 éves, a SAS légitársaság egyik igazgatójaként ment nyugdíjba, én magam 31 éve saját hitelminősítő céget vezetek. Még mindig dolgozom.”

Stockholm, 2016. május 21-én

2015. szeptember 13., vasárnap

A nyilas megszállásig voltunk ebben a házban, ahol apám testvére, Sándor Pál, lakott. Innen vitték el a feleségét, akiről többet nem hallottunk. Társbérletben laktunk, a szomszédban pedig másodunokatestvéreim laktak. Édesanyám innen menekített a Magdolna utcába, ahol a bujkáló zsidók gondnoka és gazdasági vezetője volt. Január első napjaiban súlyosan megsérült, minek következtében operációkra került sor, természetesen késve, hiszen az ostrom alatt nehezen lehetett a viszonylag közeli Baleseti Sebészetre eljutni. Haláláig gépben volt a lába. DE TÚLÉLTÜK!

2015. március 12., csütörtök

Az Én nagyszüleim voltak a házmesterek a Budapest, V. Garibaldi utca 3. szám alatt. 1942-ben kerültek oda, a ház a Hamburger család tulajdona volt (tudtommal orvos család). Nagyszüleim Szegedi János és Jánosné, Juci néni, sajnos már nem élnek. Erdélyből jöttek el, mert nem akarták felvenni a román állampolgárságot. Édesapám ebben a házban született.

2015. január 06., kedd

Az ötödik emeleten lévő műteremben (külső felirat: Nádor udvar) 1944 márciusáig-júniusáig biztosan óvoda működött, amelynek vezetője unokanővérem, Somló Ágnes volt. Amikor csillagos ház lett, Ágnes és anyja, Somló Gézáné Strelisky Anna, az utóbbinak húga, Strelisky Irén, (apám nővérei), továbbá a Strelisky család, a munkaszolgálatos Strelisky József, anyám, szül. Landauer Valéria és én, Strelisky János (akkor 7 éves) költöztünk be a nagy alapterületű, tetőablakokkal, erkéllyel rendelkező műterembe.

Itt laktunk addig, amíg a nyilasok a puccsuk után ki nem telepítettek minket onnan. Mintha néhány lakásban ott maradtak volna az addig is ott lakó "árják". Csak két további személyre emlékszem: a csinos fiatal Göndör Tesszára, és egyetlen V. emeleti szomszédunkra (Margit nénire), akinek a segítségével a nyilas puccs után 24 órát rejtőztünk a padláson apámmal, aki éppen az előző napokban kapott kimenőt. Emlékszem a tetőablakon beáradó holdfényben átolvasott éjszakákra (ha éppen nem bombáztak), meg arra a reggelre, amikor a járda szigeteken, járdákon mindenütt az "Imrédy zsidó!" felirat virított, továbbá a Margit híd felrobbantása után sebesen felhúzott palánkra, arra, amikor kis csomaggal kihajtottak minket a Szt. István parkba. Azután már nem engedtek minket vissza. Nénéimet-unokanővéremet Ravensbrückbe deportálták (megölték őket), én a Nemzetközi Vöröskereszt Gyermekotthonba kerültem, anyám az Óbudai Téglagyárból a Pestre vissza irányított "védlevelesek" csoportjával visszamenekült. A város ostromakor a tetőablakok beszakadtak, a bútorokon állt a hó.